The Beacon Chain Ethereum 2.0 explainer you need to read first

The engine was changed mid-flight! September 15 2022 — the day Ethereum switched to Proof-of-Stake.

That new engine is the Beacon Chain.

Do you feel it’s time to know a bit how it works?

Ethereum’s Beacon Chain will be illustrated with examples at the right level to make you proficient and save time.

Slots and Epochs

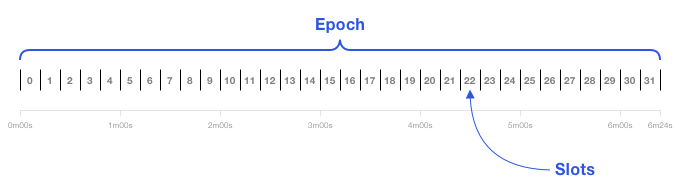

The Beacon Chain provides the heartbeat to Ethereum’s consensus. Each slot is 12 seconds and an epoch is 32 slots: 6.4 minutes.

A slot is a chance for a block to be added to the Beacon Chain. Every 12 seconds, one block is added when the system is running optimally. Validators do need to be roughly synchronized with time.

A slot is like the block time, but slots can be empty. The Beacon Chain genesis block is at Slot 0.

Validators and Attestations

While proof-of-work is associated with miners, Ethereum’s validators are proof-of-stake “virtual miners”. Validators run Ethereum’s consensus. Their incentives are discussed later in Staking Rewards and Penalties.

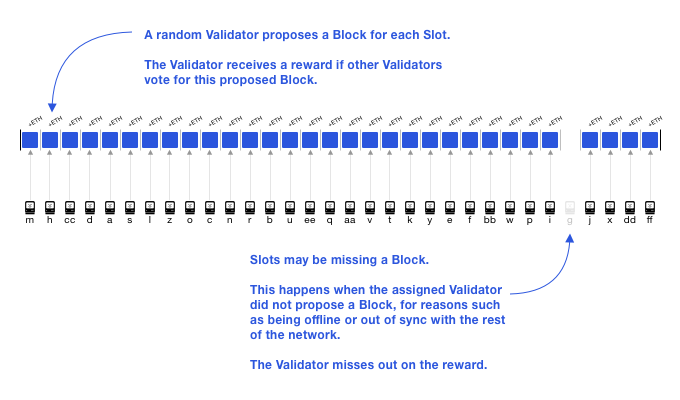

A block proposer is a validator that has been pseudorandomly selected to build a block.

Most of the time, validators are attesters that vote on blocks. These votes are recorded in the Beacon Chain and determine the head of the Beacon Chain.

At every epoch, a validator is pseudorandomly assigned to a slot.

An attestation is a validator’s vote, weighted by the validator’s balance. Attestations are broadcasted by validators in addition to blocks.

Validators also police each other and are rewarded for reporting other validators that make conflicting votes, or propose multiple blocks.

The contents of the Beacon Chain is primarily a registry of validator addresses, the state of each validator, and attestations. Validators are activated by the Beacon Chain and can transition to states, briefly described later in Beacon Chain Validator Activation and Lifecycle.

Staking validators: semantics

Validators are virtual and are activated by stakers. In PoW, users buy hardware to become miners. In Ethereum, users stake ETH to activate and control validators.

It is clearer to associate stakers with a stake, and validators with a balance. Each validator has a maximum balance of 32 ETH, but stakers can stake all their ETH. For every 32 ETH staked, one validator is activated.

Validators are executed by validator clients that make use of a beacon (chain) node. A beacon node has the functionality of following and reading the Beacon Chain. A validator client can implement beacon node functionality or make calls into beacon nodes. One validator client can execute many validators.

Committees

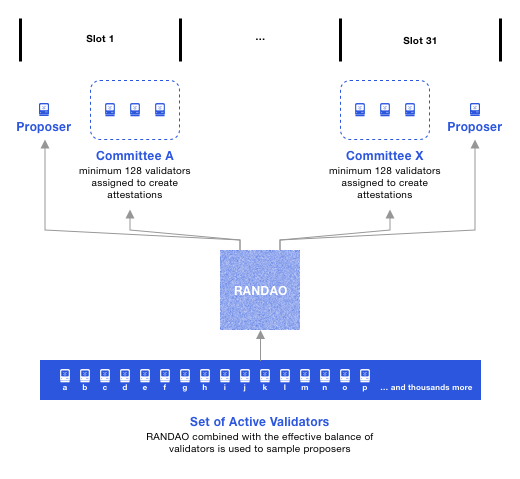

A committee is a group of validators. For security, each slot has committees of at least 128 validators. An attacker has less than a one in a trillion probability of controlling ⅔ of a committee.

The concept of a randomness beacon that emits random numbers for the public, lends its name to the Ethereum Beacon Chain. The Beacon Chain enforces consensus on a pseudorandom process called RANDAO.

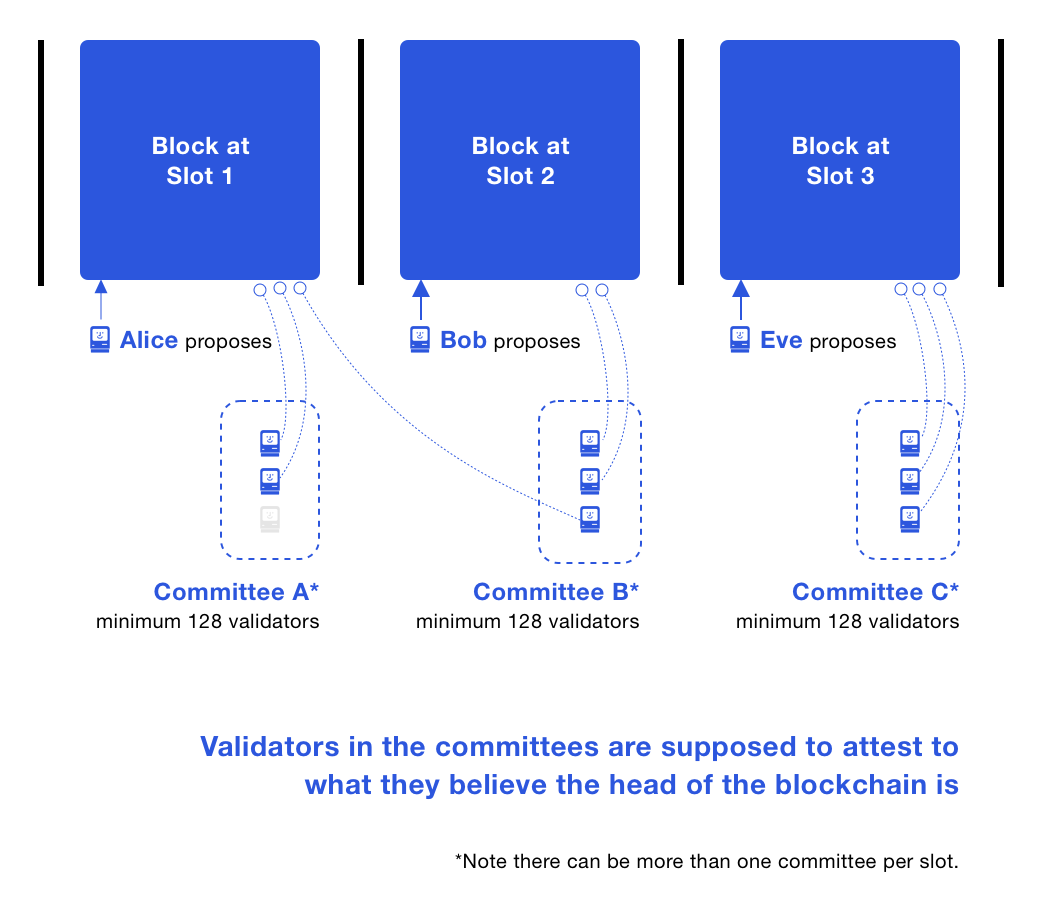

Proposers are selected by RANDAO with a weighting on the validator’s balance. It’s possible a validator is a proposer and committee member for the same slot, but it’s not the norm. The probability of this happening is 1/32 so we’ll see it about once per epoch. The sketch depicts a scenario with less than 8,192 validators, otherwise there would be at least two committees per slot.

The diagram is a combined depiction of what happened in three slots. In Slot 1, a block is proposed and then attested to by two validators; one validator in Committee A was offline. The attestations and block at Slot 1 propagate the network and reach many validators. In Slot 2, a block is proposed and a validator in Committee B does not see it, thus it attests that the Beacon Chain head is the block at Slot 1. Note this validator is different from the offline validator from Slot 1. Attesting to the Beacon Chain head is called an LMD GHOST vote. In Slot 3, all validators in Committee C run the LMD GHOST fork choice rule, and independently attest to the same head.

A validator can only be in one committee per epoch. Typically, there are more than 8,192 validators: meaning more than one committee per slot. All committees are the same size, and have at least 128 validators. The security probabilities decrease when there are less than 4,096 validators because committees would have less than 128 validators.

At every epoch, validators are evenly divided across slots and then subdivided into committees of appropriate size. All of the validators from that slot attest to the Beacon Chain head. A shuffling algorithm scales up or down the number of committees per slot to get at least 128 validators per committee.

Beacon Chain Checkpoints

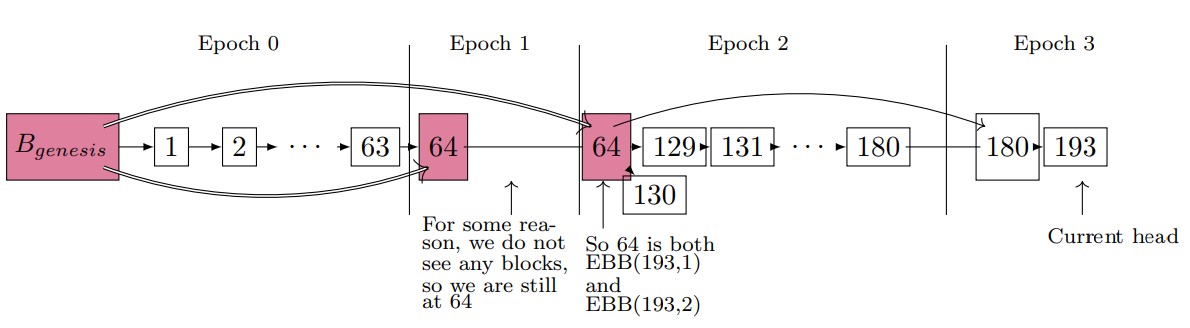

A checkpoint is a block in the first slot of an epoch. If there is no such block, then the checkpoint is the preceding most recent block. There is always one checkpoint block per epoch. A block can be the checkpoint for multiple epochs.

Note Slot 65 to Slot 128 are empty. The Epoch 2 checkpoint would have been the block at Slot 128. Since the slot is missing, the Epoch 2 checkpoint is the previous block at Slot 64. Epoch 3 is similar: Slot 192 is empty, thus the previous block at Slot 180 is the Epoch 3 checkpoint.

Epoch boundary blocks (EBB) are a term in some literature (such as the Gasper paper, the source of the diagram above and a later one), and they can be considered synonymous with checkpoints.

When casting an LMD GHOST vote, a validator also votes for the checkpoint in its current epoch, called the target. This vote is called a Casper FFG vote, and also includes a prior checkpoint, called the source. In the diagram, a validator in Epoch 1 voted for a source checkpoint of the genesis block, and a target checkpoint of the block at Slot 64. In Epoch 2, the same validator voted for the same checkpoints. Only validators assigned to a slot cast an LMD GHOST vote for that slot. However, all validators cast FFG votes for each epoch checkpoint.

Supermajority

A vote that is made by ⅔ of the total balance of all active validators, is deemed a supermajority. Pedagogically, suppose there are three active validators: two have a balance of 8 ETH, and a sole validator with a balance of 32 ETH. The supermajority vote must contain the vote of the sole validator: although the other two validators may vote differently to the sole validator, they do not have enough balance to form the supermajority.

Finality

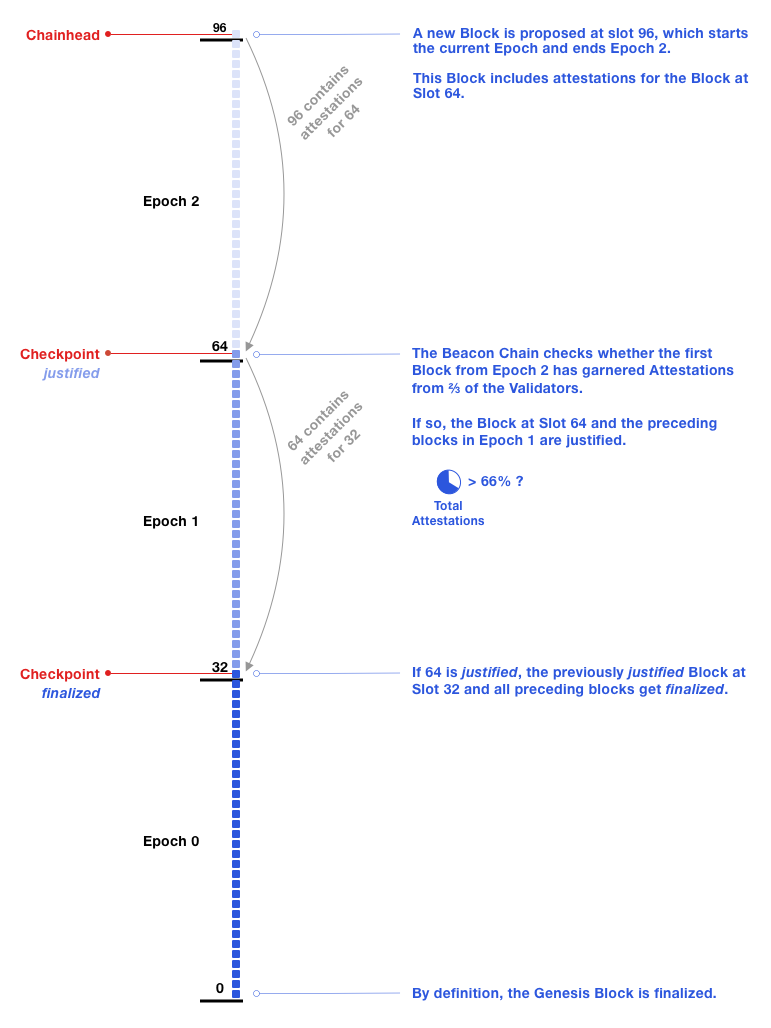

When an epoch ends, if its checkpoint has garnered a ⅔ supermajority, the checkpoint gets justified.

If a checkpoint B is justified and the checkpoint in the immediate next epoch becomes justified, then B becomes finalized. Typically, a checkpoint is finalized in two epochs, 12.8 minutes.

On average, a user transaction would be in a block in the middle of an epoch. It’s half an epoch until the next checkpoint, suggesting transaction finality of 2.5 epochs: 16 minutes. Optimally, more than ⅔ of attestations will have been included by the 22nd slot of an epoch. Thus, transaction finality is an average of 14 minutes (16+32+22 slots). Block confirmations emerge from a block’s attestations, to its justification, to its finality. Use cases can decide whether they need finality or an earlier safety threshold is sufficient.

To simplify the following narratives, assume that validators all have the same balance.

What happened at the Beacon Chain head

The epoch boundary block at Slot 96 is proposed and contains attestations for the Epoch 2 checkpoint. The number of attestations for the Epoch 2 checkpoint now reaches the ⅔ supermajority. This causes the justification of the Epoch 2 checkpoint, and thus the finality of the previously justified Epoch 1 checkpoint. The finality of Slot 32 immediately causes the finality of all blocks preceding it. When finalizing a checkpoint, there is no limit to the number of blocks that can be finalized. Although finality is only computed at epoch boundaries, attestations are accumulated at each block, as described in alternate narratives “What could have happened from genesis to the head” below.

What could have happened from genesis to the head

With the same illustration, here is a storyline that could have been observed from genesis. All the proposers from Slot 1 until Slot 63 propose a block, and these appear on-chain. With each block in Epoch 1, its checkpoint (block at Slot 32) accumulates attestations from 55% of validators. The block at Slot 64 is proposed and it includes attestations for the Epoch 1 checkpoint. Now, 70% of validators have attested to the Epoch 1 checkpoint: this causes its justification. The Epoch 2 checkpoint (Slot 64) accumulates attestations throughout Epoch 2 but does not reach the ⅔ supermajority. The block at Slot 96 is proposed and it includes attestations for the Epoch 2 checkpoint. This leads to reaching the ⅔ supermajority and the justification of the Epoch 2 checkpoint. Justifying the Epoch 2 checkpoint finalizes the Epoch 1 checkpoint and all prior blocks.

Here is another possible scenario. Consider only until Epoch 1. The checkpoint at Epoch 1 could have obtained a ⅔ supermajority before the checkpoint at Epoch 2 is proposed. For example, as the blocks in Slot 32 to Slot 54 are proposed, the attestations to justify the checkpoint (Slot 32) could have already reached the ⅔ supermajority. In this case, the checkpoint would have been justified before Epoch 2. A checkpoint can be justified in its current epoch, but its finalization requires at least the epoch after it.

The justification of a block can sometimes finalize a block two or more epochs ago. The Gasper paper discusses these cases. They are expected only in exceptional times of high latency, network partitions, or strong attacks.

Attestations: a closer look

An attestation contains both an LMD GHOST vote and an FFG vote. Optimally, all validators submit one attestation per epoch. An attestation has 32 slot chances for inclusion on-chain. This means a validator may have two attestations included on-chain in a single epoch. Validators are rewarded the most when their attestation is included on-chain at their assigned slot; later inclusion is a decaying reward. To give validators time to prepare, they are assigned to committees one epoch in advance. Proposers are only assigned to slots once the epoch starts. Nonetheless, secret leader election research aims to mitigate attacks or bribing of proposers.

Committees allow for the technical optimization of combining signatures from each attester into a single aggregate signature. When validators in the same committee make the same LMD GHOST and FFG votes, their signatures can be aggregated.

Staking Rewards and Penalties

Without getting too deep, we’ll discuss six topics regarding validator incentives:

- attester rewards

- attester penalties

- typical downside risk for stakers

- slashings and whistleblower rewards

- proposer rewards

- inactivity leak penalty

1. Validators get rewards for making attestations (LMD GHOST and FFG votes) that the majority of other validators agree with. Attestations in finalized blocks are worth more.

2. On the flip side, validators get penalties for not attesting or if they attest to blocks that are not finalized.

3. Before outlining less common penalties and rewards, you may want to know your downside risk in becoming a staker. As a staker concerned about how much ETH you may lose, it’s close to a mirror of how much you can earn. For example, if a validator stands to make 10% in a year on attester rewards, a (honest) validator stands to lose 7.5% if they do the worst job possible. A validator that is always offline or always votes on blocks that do not get finalized, will be penalized ¾ the amount that a validator would be rewarded for making punctual attestations that are finalized. The 365-day example means that falling offline for a few days or weeks, is a much smaller penalty: dropping offline for 36 days would lose around 0.75% (unless there’s an inactivity leak described below in #6).

4. Slashings are penalties ranging from over 0.5 ETH up to a validator’s entire stake. An honest, secure validator cannot be slashed by the actions of other validators. For committing a slashable offence a validator loses at least 1/32 of their balance and is deactivated (“forced exit”). The validator is penalized as if it was offline for 8,192 epochs. The protocol also imposes an additional penalty based on how many others have been slashed near the same time. The basic formula for the additional penalty is: validator_balance*3*fraction_of_validators_slashed. An effect is that if ⅓ of all validators commit a slashable offence in a similar period of time, they lose their entire balance. The validator that reports a slashable offence gets a whistleblower’s reward.

5. Proposers of blocks that get finalized, obtain a sizable reward. Validators that are consistently online doing a good job accrue ~1/8 boost to their total rewards for proposing blocks with new attestations. When a slashing happens, proposers also get a small reward for including the slashing evidence in a block. Currently, all of the whistleblower’s reward actually goes to the proposer.

6. Ethereum is a system with many mechanisms, some that can be appreciated more by their overall effects. The designed rewards and penalties culminate in an inactivity leak penalty. This is severe and rare unlike typical risks in #3. Basically, if there have been more than four epochs since finality, validators suffer an inactivity penalty that increases quadratically until a checkpoint is finalized. The inactivity penalty (or “quadratic leak”) guarantees this type of outcome: if 50% of validators drop offline, blocks will start finalizing again after 18 days. The quadratic leak drains problematic validators to a forced exit so that other validators will become a ⅔ majority that can resume finality. The inactivity leak does not drain validators that are operating optimally. During an inactivity leak, attester rewards are zero; validators earn proposer and whistleblower rewards as usual.

Slashable Offences

There are four slashing conditions for validators. They can be described as a double proposal, an LMD GHOST double vote, an FFG surround vote, and an FFG double vote.

A double proposal is a proposer proposing more than one block for their assigned slot.

Similarly, an LMD GHOST double vote is a validator attesting to two different Beacon Chain heads for their assigned slot.

A surround vote is a validator casting an FFG vote that surrounds or is surrounded by a previous FFG vote they made. Here are two examples based on a scenario that a validator made an FFG vote in Epoch 5 with a source of Slot 32 and target of Slot 128:

- An FFG vote in Epoch 6 with a source of Slot 64 and target of Slot 96, would be an FFG vote that was surrounded by their Epoch 5 vote.

- An FFG vote in Epoch 6 with a source of Slot 0 and target of Slot 160 would surround their FFG vote in Epoch 5.

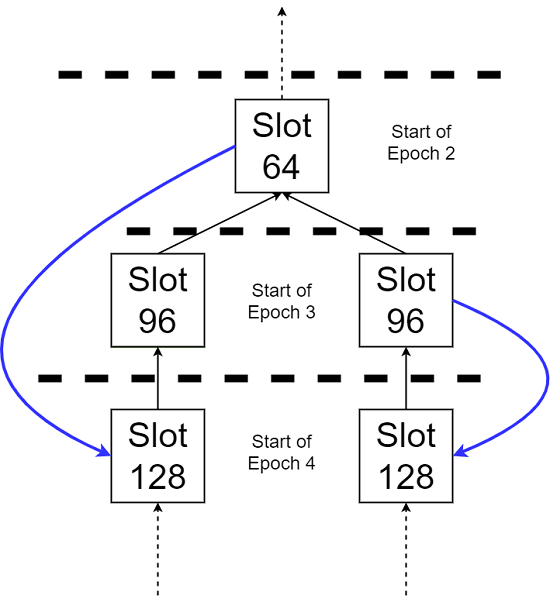

An FFG double vote is a validator casting 2 FFG votes for any two targets at the same epoch. This can happen during a fork.

The blue arrows are two FFG votes, one voting for a target block at Slot 128 on the left fork, and another voting for a target block at Slot 128 on the right fork. A validator casting both votes, commits a slashable offence called double voting. Above is an example of a double vote where the source checkpoints are different.

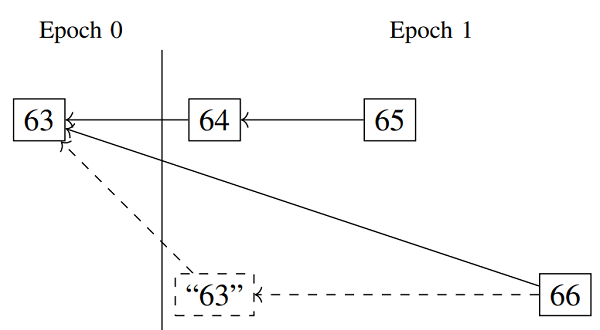

Next, a scenario where a double vote has the same source (Epoch 0 checkpoint) and the targets are different.

The upper fork has an Epoch 1 checkpoint of “block 64”. The lower fork has an Epoch 1 checkpoint of “block 63”. (Because there was no block proposed at Slot 64 in the lower fork; recall the section on Beacon Chain Checkpoints.) Voting for an Epoch 1 target of “block 64”, and an Epoch 1 target of “block 63”, is a double vote. A double vote is when a validator casts FFG votes for two targets at the same epoch.

An intuition behind slashing double votes is so that validators vote for one chain, rather than two or more forks.

Note that an attestation, because of how they can be aggregated, can appear to be more than one vote. The same attestation can appear in different aggregates, but it is still the same attestation and not a double vote.

A whistleblowing validator needs to include the conflicting votes to prove that another validator should be slashed. Efficiently finding a conflicting vote among a large history is an algorithms and data structures challenge (linked in the conclusion).

A validator is in total control to avoid getting slashed: it only needs to remember what it has signed. An honest validator cannot be slashed by the actions of other validators. As long as a validator does not sign a conflicting attestation or proposal, the validator cannot be slashed.

A validator client may use multiple beacon nodes for factors like better uptime, trust, and Denial of Service protection. In these setups, or where a backup validator client is used, users need to be careful that the validator does not sign conflicting messages.

Beacon Chain Validator Activation and Lifecycle

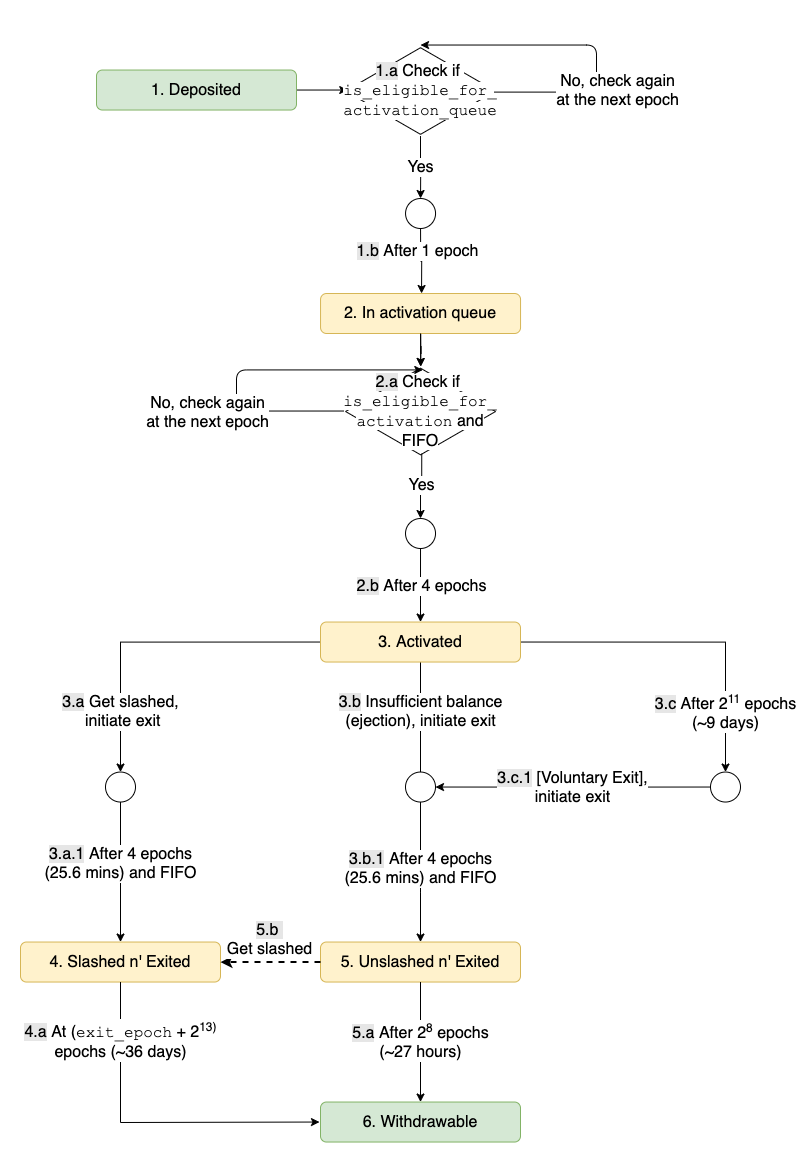

Each validator needs a balance of 32 ETH to get activated. A user staking 32 ETH into a deposit contract on Ethereum mainnet, will activate one validator.

The Beacon Chain deactivates (“forced exit”) all validators whose balance reaches 16 ETH; stakers will be able to withdraw any remaining validator balance likely in 2023.

Validators can also “voluntary exit” after serving for 2,048 epochs, around 9 days.

In any voluntary or forced exit, there is a delay of four epochs before stakers can withdraw their stake. Within the four epochs, a validator can still be caught and slashed. An honest validator’s balance is withdrawable in around 27 hours. But a slashed validator incurs a delay of 8,192 epochs (approximately 36 days).

Further technical details are described in A note on Ethereum 2.0 phase 0 validator lifecycle including this flowchart:

To avoid large changes in the validator set in a short amount of time, there are mechanisms limiting how many validators can be activated or exited within an epoch. For example, these make it more difficult to activate many validators quickly to attack the system.

The Beacon Chain uses a deeper concept of effective balances which change less often than validator balances and enable technical optimizations.

Wrapping Up

At every epoch, validators are evenly divided across slots and then subdivided into committees of appropriate size. Validators can only be in one slot, and in one committee. Collectively:

- all validators in an epoch attempt to finalize the same checkpoint: FFG vote

- all validators assigned to a slot attempt to vote on the same Beacon Chain head: LMD GHOST vote

Optimal behavior rewards validators the most.

The Beacon Chain genesis was on December 1 2020 with 21,063 validators. The number of validators can decrease with slashings or voluntary exits, or stakers can activate more. Approaching 2 years, there are over 400,000 validators.

The world’s never had a scalable platform for decentralized systems and applications before. If you’re inspired to dive deeper, authoritative references are in Ethereum Proof-of-Stake Consensus Specifications. It includes the Beacon Chain spec, links to other key resources, and issues with bounties. Contribute or refer others to challenges, ethresear.ch or the Ethereum Magician’s forum, and be a part of making history!

Thank you to Danny Ryan for review and feedback on several sections, Momo Araki for the massively helpful diagrams, and all others consulted. Banner image derived from original by Hsiao-Wei Wang. Please share or tweet this explainer if it’s been helpful to you :)

Updates 2022-12-12: Added “LMD GHOST double vote” slashing, thanks to Jiasun, Barnabé, and Ben.

2022-10-01: Removed sharding, crosslinks, and old terms like eth2. Improve opening and conclusion. See archive.org for prior versions.

2020-05-23: Staking Rewards and Penalties are clarified further and per v0.12 of the Beacon Chain spec, optimal validators are not drained by the inactivity leak.

2020-04-27: Fix explanation of double vote. Thank you Aditya Asgaonkar for reporting, review, and check out his posts like Casper FFG Explainer.